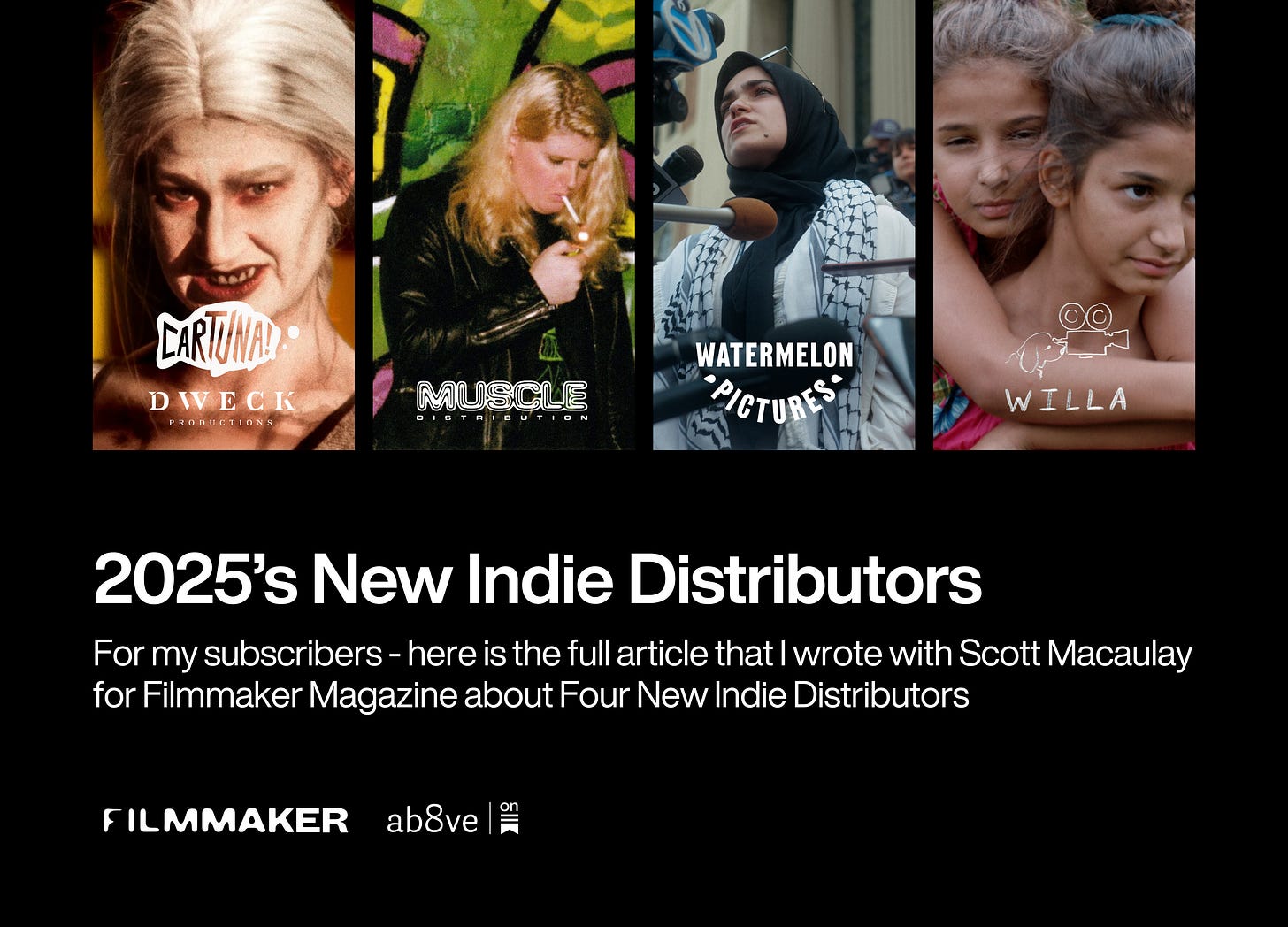

2025’s New Indie Distributors

For my subscribers - here is the full article that I wrote with Scott Macaulay for Filmmaker Magazine about Four New Indie Distributors

Written by Jon Reiss and Scott Macaulay for Filmmaker Magazine

This was first published in the June issue of Filmmaker Magazine - but I have a feeling that perhaps some of my subscribers did not see it there. For those of you have not seen it - here it is in all its 4000+ word glory.

The crisis in independent film distribution started in 2007/08, when the global financial crisis hit; acquisitions plummeted and studios shuttered their specialty divisions. Since then, fewer and fewer filmmakers have walked away from festivals and markets with satisfactory distribution deals. This crisis has led to more of them pursuing an independent path to distribution, either by choice or necessity, but it’s also led to newer companies embracing social media and sophisticated psychographic marketing, such as A24, NEON and MUBI.

Now in the mix are a fresh crop of smaller distributors, such as the ones profiled here, reinventing the filmmaker/distributor partnership. Each of these companies sees theatrical runs not as optional, but as essential: event screenings, community Q&As and creative stunts aren’t just marketing—they’re the heart of audience engagement. Watermelon and Willa share an impact focus. Cartuna x Dweck wants to create carnival-like theatrical experiences with inventive marketing, and Muscle operates deep within queer grassroots ecosystems and seeks to build cultural cachet for its releases.

For this new wave of distributors, audience building isn’t about scale—it’s about specificity. Rejecting the generic blast radius of traditional marketing, these companies are meeting audiences where they already are: in their communities, subcultures and inboxes. These distributors aren’t just reshaping where films go—they’re rethinking how filmmakers are treated throughout the process, emphasizing transparency, flexibility and fairness. They vary in scale from Watermelon Pictures—born from a traditional home video company, MPI, and starting its own progressive streaming service—to Muscle, the scrappiest of the bunch, with no overhead, no staff, and just one founder running on curatorial instinct and community credibility. The rise of these new distributors is a hopeful salve to the often depressing narrative around our ecosystem.— Jon Reiss

Watermelon Pictures

Launched in 2024 by Palestinian American brothers Hamza and Badie Ali, Watermelon Pictures is proving that boldness, strategy and community can coexist—even thrive—in the face of adversity. What began as a response to genocide and erasure has grown, in little more than a year, into one of today’s most forward-thinking, culturally rooted distributors.

Watermelon’s story starts with MPI Media Group, the independent distribution company founded in 1976 by the brothers’ father Malik Ali and their uncle Waleed Ali. Over the decades, MPI became known for its genre division, Dark Sky Films; physical media catalog; and fierce independence. In the aftermath of October 7, 2023, Hamza and Badie moved quickly to launch a company dedicated to Arab ownership, cultural representation and political accountability in film distribution. “[Watermelon] was something my brother and I had been discussing in recent years, and it became expedited by the ongoing situation—the genocide unfolding in the Middle East—and seeing the dehumanization and lack of representation,” says Badie. “Being probably the only Arab-owned film distribution company in North America, we felt it was incumbent on us to help the stories that are out there receive proper distribution.”

Watermelon is fully family owned and funded internally—no venture capital, no grants—and its mission is rooted in three pillars. It elevates Palestinian, Global South and underrepresented narratives; ties its screenings to grassroots organizing, dialogue and direct action; and commits itself to deal and accounting transparency. As head of production and acquisitions Munir Atalla put it in our conversation: “We want to offer top-shelf distribution and artist-first partnerships. You shouldn’t have to choose.”

Watermelon operates as a traditional all-rights distributor, taking theatrical, digital, educational and streaming rights. Their strategy blends windows: a robust theatrical first, followed by educational and community events, then VOD. Their theatrical screenings are deeply event-ized, often hosted by student organizations and followed by talkbacks, dinners or processing circles. For the campus protest doc The Encampments, Watermelon held screenings directly at campus protest encampments. At other events, attendees migrated from the cinema to Palestinian restaurants for shared meals and discussion.

The results so far are impressive. There were more than 100 community screenings of The Encampments; still in theaters, at press time its theatrical box office surpassed $500,000. Another picture, From Ground Zero, topped $350,000, playing both multiplexes like AMC and Regal as well as independent houses like New York’s Angelika. VOD revenue for that title has hit six figures, outperforming expectations.

Watermelon’s digital strategy centers on platforms like Instagram (more than 225,000 followers) and TikTok, where the company’s creative director, Alana Hadid, connects with a network of micro-influencers. Watermelon has also built internal marketing infrastructure, adding more than 15 team members in less than a year. Half of those hires focus specifically on marketing, content creation and outreach. They still hire outside designers, editors and publicists, but the core of the work is now in-house. And while political content often gets flagged by Meta and Google, Watermelon adapts by relying on earned media, organic engagement and community. It has yet to run a paid ad for The Encampments—and still sold out major venues.

In 2025, Watermelon soft-launched its own SVOD/TVOD platform, Watermelon+, to serve as a curated home for Palestinian and adjacent cinema. Programming contains curated thematic collections from decades of Palestinian filmmaking; exclusive premieres, like The Teacher, with a three-week window before any other platform; and TVOD and SVOD integration (i.e., viewers can subscribe or rent à la carte). The long-term ambition is for Watermelon+ to become an interactive hub with user reviews, sneak previews and community decision-making on future titles. It’s early, but the goal is clear: meet the audience that the large streamers won’t. As Atalla put it, “If legacy platforms are too afraid to touch these stories, we’ll do it ourselves.”

In terms of its deals, Watermelon takes a 30- to 35-percent distribution fee off the gross. Expenses are limited to third-party only; there’s no recouping of internal overhead. Generally 100% of net profits go to the filmmakers (sometimes the split is 90/10, or 80/20), and often minimum guarantees are offered. These can reach the six figures, despite a lack of market competition. On Watermelon+, the revenue share is a flat 50/50 based on viewership. The company is open to rights carve-outs (airlines, TV, etc.) and flexible on exclusivity, especially for the streaming platform.

Watermelon is also nimble. It signed onto The Encampments early, “before that film was even edited together into an assembly,” says Atalla. “We were planning to release it in the fall, but when one of the main protagonists of the film, Mahmoud Khalil, was abducted by ICE, we felt an obligation to release it. After a lot of thoughtful consideration and consulting with the people involved, including his family and other students, we decided to release it, and in just 10 days it was premiering at the Angelika. That turnaround wouldn’t have been possible if we had to do the festival circuit.”

Films like The Encampments and From Ground Zero have drawn coordinated opposition campaigns from groups like Christians United for Israel. Some theaters were inundated with letters demanding cancellation, but none of them pulled the bookings. In fact, theaters like Angelika doubled down, emboldened by the turnout and by the chance to serve younger, politically active audiences they’d never reached before.

With films like The Teacher; Sudan, Remember Us and The Glassworker on deck, Watermelon is poised to expand its content beyond Palestine. The plan includes more narrative films, genre titles and eventually TV, cooking shows and reality programming. It’s all about building a progressive, BLM, Global South media-oriented ecosystem. As Badie put it: “We’re trying to shift culture. Not just for Palestine. For everyone.” Watermelon is proof that distribution can be ethical, scalable and transformative.—JR

Willa

What if distribution wasn’t the afterthought, but the plan from the beginning? That question sits at the core of Willa, a bold production and distribution company founded by Elizabeth Woodward. Born from the producer’s personal experience and frustration with the status quo, Willa is reimagining how socially important films get seen—and sustained.

Willa was created after Woodward premiered Dina Amer’s You Resemble Me, about a French-Moroccan woman falsely accused of being a suicide bomber, at the Venice Film Festival. She remembers, “We got incredible reviews. Spike Lee, Spike Jonze, Alma Har’el, Riz Ahmed and Claire Denis all joined as executive producers. We built out a whole strategy for our impact campaign and audience engagement. But the distribution offers that we got through a major agency felt like more of a burial than a release.”

Rather than settle for a trade headline and slow fade, Woodward mapped out her own release strategy. The result: 85 theatrical markets, top arthouse cinemas and a powerful grassroots impact campaign. “We did a lot of non-theatrical screenings and built out a robust impact campaign with dozens of partner organizations,” Woodward says. “We gave the film the same dynamic life in the distribution phase that we created for the production phase.” In raising additional investment as well as landing grants, Woodward says Willa thought about distribution through multiple lenses: “How do we make revenue for the film in order to pay the investment back? How do we make an impact and make sure the right audiences see the film? Raise awareness and shift perspectives but also launch Dina’s career as a filmmaker in a dignified way?”

She followed You Resemble Me with her next production, Another Body, a documentary about deepfake abuse directed by Reuben Hamlyn and Sophie Compton. (Filmmaker editor-in-chief Scott Macaulay is a consulting producer on Another Body.) When that film also received lackluster offers, she partnered with Utopia for a hybrid rollout, anchored by a pay-what-you-can summit on deepfake abuse—“We learned a lot about audience behavior,” she says—and garnered Emmy nominations and viral attention.

Another Body had gone through Catalyst, Sundance’s film financing program, and Woodward was subsequently invited to a Catalyst distribution fellowship program, Future Models. With distribution veterans such as Arianna Bocco (currently head of global distribution at MUBI), Holly Gordon (chief impact officer at Participant) and Alex Simon (director, media portfolio and storytelling partnerships, Emerson Collective) as mentors, she workshopped the strategy of a formal distribution company that would distribute films beyond her own portfolio.

Willa is built on a hybrid financing structure: traditional, recoupable P&A investments paired with non-recoupable philanthropic capital. (Notably, Woodward has raised these philanthropic funds to support the company’s entire slate, not just individual titles.) This two-pronged approach allows Willa to fund robust theatrical releases as well as high-touch impact campaigns without having to compromise one for the other. “Philanthropy supports being able to take the necessary risks to do pilot experiments,” says Woodward, such as experimental pricing, eventized screenings and new outreach models. Running the impact campaign work in-house, and with the same team, ensures complete coordination across the release.

Every filmmaker who works with Willa is invited to a paid “strategy sprint”—one week of “design and ideating,” as well as education. Filmmakers are given a reading list covering the distribution process and then are encouraged to dream. “The Willa team’s role is to present all this [information] in a very succinct way: ‘These are all the things that are possible that we know about,” says Woodward. “We can do any of those things, or we could invent something completely new together, and we’ll help figure out logistically how it can happen.’” From there, filmmaker involvement is flexible, from full collaborator to trusting partner.

Willa monetizes across theatrical, educational, TVOD, community screenings, airlines/cruises and more experimental avenues like Kinema, Eventive merchandise and branded partnerships. Brand sponsorships in particular are becoming a growing part of Willa’s toolkit. P&A is recouped first, then a distribution fee (which includes company overhead) is applied, followed by profit splits—often in favor of the filmmaker, especially when rights are shared or windows are limited. Terms so far have ranged from five to 10 years. Carve-outs for rights like educational are possible, and Willa actively connects filmmakers with partners when they’re not the best fit.

Currently, Willa’s slate is intentionally tight. Alonso Ruizpalacios’ La Cocina, starring Rooney Mara, is on digital platforms — including streaming on MUBI — after a theatrical run. Fawzia Mirza’s The Queen of My Dreams was recently co-released with marketing firm Product of Culture. Woodward learned about the film after appearing on a panel with one of its producers, Andria Wilson Mirza, and had the idea of co-buying the film with Product of Culture, “who are hired by all the studios and streamers to focus on specialty marketing for South Asian films.” Its founders, says Woodward, “were lamenting about how there are so many independent South Asian films not getting the love and support they need from distribution companies. When they told me what their work is, I said, ‘Do you realize that you do 70 percent of what a distributor does already?’” The Queen of My Dreams release is something of a “case study,” says Woodward, giving both companies new experience that could inform future releases.

“My hope is that if more producers can be involved in the distribution space and leave that experience feeling empowered, then they will want to build a distribution part of their own production companies,” Woodward concludes. “I have been gaslit so intensely through[out] my career that being able to help ‘de-gaslight’ fellow filmmakers about this entire chapter of a film’s life gives me a huge degree of satisfaction,” she says. “I’m all about trying to work together to make this world better to the best of our ability, and that wasn’t happening when I got dunked into the distribution world.”—JR

Muscle

Recounting the short history of her new distribution company, Muscle, Elizabeth Purchell cites two conversations as formative. The first, in 2024, was with Yellow Veil Pictures co-founder Joe Yanick. Purchell had just moved to New York from Austin, where she had been working freelance for several years on home video releases—writing booklet copy and creative advertisements and producing the discs—as well as programming genre and sex-themed films for local theaters. Those jobs led into a full-time position at the American Genre Film Archive, a not-for-profit genre film theatrical and home video distributor. “The staff there is so small, and it’s such a DIY organization,” she says. “I learned how to make DCPs and how booking and print traffic work.” After about a year in the job, she decided to move “out of Texas to New York. I’m trans, and it’s really bad down there right now.” Remote work for AGFA followed until she was abruptly laid off. “With the job market in the industry being so bad, especially for someone who likes the very niche things I do, I was trying to figure out how to keep going. Should I just make film a hobby again?”

That’s when Yanick, over coffee, said, “Well, why don’t you start your own company?” “I had been kind of thinking about it a little, but that really set the fire under me,” says Purchell. “Almost exactly one year after the layoff, the company launched, and the first release is happening now.”

That release is Haydn Keenan’s 1983 Australian cult film Going Down, a New Wave (music)-inflected drama about four female friends partying on their last night in Sydney together before one leaves for New York. (“Starstruck, but make it gay and horny and loud and in your face,” wrote critic Justin LaLiberty on Letterboxd.) Shown at Sundance in 1986, the film never received a U.S. release. Following a run at New York’s BAM, Purchell has it booked in Austin, Dallas, Seattle, Los Angeles, Toronto and other cities before a physical media release in early 2026.

The second conversation was with trans filmmaker Louise Weard, who had been self-releasing her Castration Movie—“a four-and-half-hour, hi-8 ’scope trans-misery cringe-comedy,” describes Purchell—on Gumroad and through screening venues ranging from cinema clubs in Scotland to projecting on the wall outside an anarchist co-op in Seattle. Until this point, Muscle was repertory-only; in addition to releases like Going Down, Purchell has been handling theatrical distribution for Distribpix, one of the world’s largest adult film production and distribution companies, representing films by Radley Metzger and Gerard Damiano, among others. When Weard and Purchell had lunch in New York following a Castration Movie screening, the director surprised Purchell by asking, “‘Do you want to distribute the movie?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah, of course. That’s how I went from being a repertory distributor to kind of an all-over-the-place distributor.”

Regarding Muscle’s business model, Purchell explains, “I come out of the home video world, which is a subsection of the overall cinephile scene. But I want my films to reenter the cultural conversation in a way that films generally do not do with home video.” Purchell cites Arbelos Film’s theatrical re-release of Toshio Matsumoto’s Funeral Parade of Roses, “which is now playing all over the place and one of the canonical trans films,” as an inspiration. Thus, Muscle “does full theatrical releases, then focuses on digital, then has physical media be the final step.” Disc manufacturing and distribution is handled by OCN, Vinegar Syndrome’s sister company. As for placing Blu-rays last in the release plan, Purchell says, “I really gravitate to niche, obscure films, and I can’t really expect someone to pay $30 for something they’ve never heard of before.”

Right now, Muscle is a one-person operation. For Going Down, the company paid a minimum guarantee, but that’s not usually the case for Muscle’s other titles. The filmmaker/distributor split will shift if there’s an MG, but generally, it’s 50/50 across the board. Marketing and publicity costs come off the top, and expenses are also very low—for example, just $1,000 to open Going Down, which included a publicist and a digital poster. (The latter was made by a silk-screen designer, Ashley Hohman, specializing in bootleg music and film T-shirts and who based the design on the work of 1970s Australian political poster collectives.)

Next up for Muscle is Castration Movie’s release, which begins with a U.S. festival premiere at Frameline this month. Of the release, Purchell says, “We are really going to try for more of a mainstream audience, which is kind of insane to say.” But not only does the movie have a “gimmick”—its length, and the fact that it’s just part one of an eventual 16-hour film— “the movie itself is actually great. People who come into it thinking it’s just going to be a dumb gimmick are shocked because it’s incredible.”

Other forthcoming releases include Henry Hanson’s “mumblecore trans nightmare drama,” Dog Movie; a series of EZTV-related home video and Blu-ray releases and what will be the first commercial release of cult pioneer Doris Wishman’s last film, Dildo Heaven, which screened in 2002, just before Wishman’s passing, at the New York Underground Film Festival.

“I’ve built up kind of a name for myself as a programmer and historian,” Purchell says. (She still regularly hosts screening series at New York’s IFC Center, Austin Film Society and Alamo Drafthouse Brooklyn. Other cult cinema bona fides include a Herschell Gordon Lewis She-Devils on Wheels tattoo.) “So, putting my name upfront with the company has helped a lot. I think people generally trust me and my taste. They know that if I’m releasing something they should maybe pay attention to it.”

“To me, distribution is the galaxy brain version of programming,” Purchell concludes. “It’s not that I want to show this film to my audience. It’s that I want to show this film to every audience I can show this film to.”—Scott Macaulay

Cartuna x Dweck

“As producers, we’re used to our Rolodex of financiers changing constantly because there doesn’t feel like there is a great model, or a lot of opportunities, right now to make your money back on these small films,” says Hannah Dweck, referring to the kinds of pictures—among them, We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, The Adults and Christmas Eve at Miller’s Point—she produces and finances with partner Ted Schaefer at Dweck Productions. Animation studio Cartuna founder and CEO James Belfer, who is a producer of films such as OBEX, Strawberry Mansions and Nuts! concurs: “There are just so few buyers that deals aren’t that great, especially for some of the weirder or more interesting films out there.”

The trio’s mutual frustration, coupled with a belief that they can do theatrical distribution better, at least for boundary-pushing, idiosyncratic auteur pictures, has led to a new partnership, Cartuna x Dweck, that aims to release three to four pictures a year. First up is Grace Glowicki’s Sundance premiere Dead Lover, a truly unusual blend of Stuart Gordon-style splatterpunk and The Living Theatre about a lonely gravedigger and her reanimated paramour.

With plenty of grisly gore and bodily decomposition, it’s a film that lends itself to creative marketing, such as, Belfer muses, a six-foot finger as a lobby cutout, a Smell-O-Vision release or even a Dead Lover perfume line. Belfer, who still holds onto The Human Centipede–branded staple remover he got at that film’s New York premiere, says that “smaller theaters are very game” for these kind of outrageous promotional materials but don’t get them often from smaller distributors.

As a small shop with low overhead, Cartuna x Dweck won’t initially have in-house marketing and publicity teams, choosing instead to find the right vendors for each film. Their first choice is an auspicious one, with Kurt Ravenwood, producer of Hundreds of Beavers, consulting on Dead Lover’s marketing strategy. Schaefer says, however, not to expect the “beaverfication” of every film on the Cartuna x Dweck slate. Instead, the company will draw on the larger lessons of the Hundreds of Beavers phenomenon: “How can we find the things that attract the audience for this movie, which is not the same audience as Hundreds of Beavers, necessarily? We will find new ways to get to that audience.”

Ravenwood enters the partnership having already worked with Belfer; Cartuna made its first foray into Blu-ray distribution with Hundreds of Beavers, which has sold more than 10,000 copies. Cartuna then began handling VOD for other titles on its slate, making theatrical distribution, and the Dweck partnership, the next logical step. The company took shape after Belfer and Schaefer met up at a New York party. Belfer explained how he was investing in distribution. Schaefer said he and Dweck were thinking of doing the same. They vowed to “go to Sundance and see if something piques our interest,” says Belfer, “and when we saw Dead Lover, we’re like, ‘OK, this is it.’”

Regarding Cartuna x Dweck’s approach, all three are quick to note that the company won’t be reinventing the distribution wheel so much as committing to fair terms, working closely with filmmakers on the releases and banking on theatrical. The distributor will offer filmmakers both minimum guarantees as well as gross corridors. About the partnership’s theatrical release and windowing strategy, “A good theatrical [release] can prove valuable for SVOD down the road,” says Schaefer. “We’re looking at doing road shows before theatrical. Things that event-ize the experience, drum up support and get people talking can be really effective leading into a more standard release in the major cities. Also, there are smaller, stranger theaters all over the country that want to play these types of movies but don’t always get the opportunity to. A lot of the time, our strategy will be, how can we build a longer runway before we go to SVOD, so that the film has a chance to catch on? And just because something was in theaters and had to leave for two months because the theater was booked doesn’t mean you can’t bring it back. It goes back to being nimble and proactive and finding ways to get audiences and theaters excited.”

“I think we’re in the midst of the ‘vinylification’ of film,” adds Belfer, “where theatrical is going to be almost more important and lucrative than streaming, and Blu-ray could be more lucrative than a streaming deal, too.”

Cartuna x Dweck will be committed to transparency when it comes to expenses, reporting and strategy, according to the three principals. Says Schaefer, “Having come from the producing side of things, it’s frustrating when you see an [income] report and it’s like Greek—hard to decipher and with vague terms that don’t really let you know what they’re spending money on. Most filmmakers want to be as involved as possible in the distribution of their film. Let them be part of the process.”

Since the announcement of the Cartuna x Dweck partnership in March and the acquisition of Dead Lover, the company has, says Dweck, been approached by film agents and reps. In terms of sourcing potential acquisitions, “because of the many hats we wear, we hear about many films early on.” She and Schaefer also stress that Cartuna x Dweck won’t necessarily be distributing films Dweck produces. “We’ll review a [Dweck production] just like we’d review any movie,” adds Schaefer. “It would have to make sense for both parties.”

Ultimately, the trio’s producer DNA propels a mission statement more about a sustainable ecosystem than individual titles. “People have said to us that investors should stop thinking about making their money back on small films,” says Dweck. “Which, to us, is kind of ludicrous. This is a business, after all, and we’re just trying to come up with a model that we feel works for this scale of film.”—SM

This was very inspiring, thank you. Love the creativity. If these are "unprecedented times," we need more unprecedented solutions like these companies are trying.